Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky (September 5 [17], 1857, Izhevskoye, Ryazan province – September 19, 1935, Kaluga) was a Soviet self-taught scientist who developed theoretical issues of cosmonautics, a thinker of esoteric orientation, engaged in philosophical problems of space exploration.

He came from a noble family of the Yastrzhembets coat of arms. Almost completely deafened in childhood as a result of scarlatina, Tsiolkovsky did not receive a systematic education (he studied four years in the Vyatka gymnasium and three years of self-education). In 1879 he passed the examination for the title of public teacher and until 1921 he taught mathematics and physics in schools in Borovsk and Kaluga, at the same time trying to interest the scientific community with his projects of airplanes and all-metal airship, and later – and rocket technology. He published many works at his own expense, including those devoted to substantiating the idea of cosmic pantheism.

Tsiolkovsky rose to the rank of collegiate assessor (1889), for his teaching successes he was awarded the Order of St. Stanislaus of the third degree (1906). In 1920 he became a member of the Russian Society of Amateurs of World Studies, was awarded a personal pension of the Soviet government, and in 1932 – the Order of the Red Banner of Labor.

In his science fiction works, being a supporter and propagandist of the ideas of space exploration, Tsiolkovsky proposed to populate outer space with the use of orbital stations, put forward the ideas of space elevator, hover trains. He believed that the development of life on one of the planets will someday reach such power and perfection, which will overcome the forces of gravity and spread life throughout the universe. He considered the elevation of intellectuals and the breeding of a humanity devoid of passions but with a great intelligence that would make possible the realization of a “rational pacified existence” as a necessary step toward the dispersal of humanity in the cosmos. This esoteric utopia of Tsiolkovsky provided the leading impetus for the development of the foundations of rocket and space technology.

Tsiolkovsky also substantiated the use of rockets for flights into space, even in the 1920s came to the conclusion about the need to use “rocket trains” – prototypes of multistage rockets, comprehended the issues of human survival in weightlessness during long space flights. His main scientific works – on aeronautics, rocket dynamics and cosmonautics – began with an attempt to use the mathematical apparatus to solve fantastic problems. Many researchers, including Ya. Perelman, characterized Tsiolkovsky as a thinker significantly ahead of his time.

A powerful stimulus for the study of Tsiolkovsky’s achievements was the beginning of the space age, which coincided with his centenary, celebrated in 1957. There are monuments to Tsiolkovsky in Kaluga and Moscow, his house-museum in Kaluga, and museums in other cities. In 1954 the Tsiolkovsky Medal was established. Tsiolkovsky Medal. In 1961, a crater on the back side of the Moon was named in the scientist’s honor, and in 2015, a city at the Vostochny Cosmodrome under construction was named after him.

Biography

Origin. Early years (1857-1868)

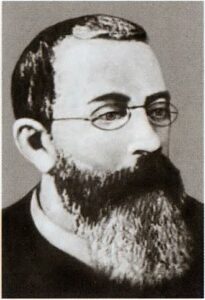

Eduard Ignatievich Tsiolkovsky – father

Maria Ivanovna Yumasheva – mother

In the autobiographical manuscript “Traits of my life”, written in 1935, K. E. Tsiolkovsky claimed that his father had “…kinship with Nalivaiko”. It is known that the noble family of Tsiolkovsky of the coat of arms Jastrzhembets was mentioned from 1697 in Tsiolkovo, Płock voivodeship. In the same year the ancestor – Jacob Tsiolkowski – participated in the session of the Sejm at the election of the Polish king August II. Representatives of the family owned the villages Velikoye and Maloye Tsiolkovo until 1777. After the first partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth the great-grandfather – Thomas Tsiolkovsky – parted with his possessions and moved to Zhitomir region. In the Russian Empire in 1786, Ignatiy Fomich Tsiolkovsky – the grandfather of the future scientist – was born. His youngest son, named in Polish Makary Eduard Erasmus, was born on March 31, 1820. By decision of the Governing Senate on May 28, 1834 Eduard was given a certificate of noble origin, which allowed him to enter the Forest Institute. In 1841, Eduard Ignatyevich Tsiolkovsky graduated from it with the rank of warrant officer of the second category.

E. I. Tsiolkovsky served in Vyatka province, and from 1843 – in Ryazan, in Pronsky uyezd. In the village of Dolgoi he met small noblemen of Tatar origin Yumashevs, who also owned a cooperage and basket workshop. In January 1849, he married their daughter Maria Ivanovna according to the Orthodox rite. In the summer of the same year, Eduard Tsiolkovsky was transferred to Spassky district in the village of Izhevskoye, where their children were born in a house on Polnaya Street (now Tsiolkovsky). According to the memories of his son, Eduard Ignatievich was by nature gloomy, cold, restrained, and rarely showed his feelings in public; however, once he and his wife had a spat of such force that Tsiolkovsky senior wanted to part with her. According to the same memoirs, his father “moderately drank”, smoked all his life. Having received a practical education, he did not know foreign languages (except Polish, and read Polish newspapers), was not characterized by religiosity, and was not a Polish patriot; in the house always spoke Russian[Note 1]. Shortly before his death, Eduard Tsiolkovsky became interested in the Russian Gospel, possibly under the influence of Tolstoyism. According to the same memoirs of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, his mother did not live to the age of forty, having suffered 13 difficult pregnancies. Of the children survived seven – two daughters and five sons, including Konstantin himself, born September 5 (17), 1857.

During the periods 1860-1868 and 1878-1881, the Tsiolkovsky family lived in Ryazan, occupying several rooms in the city’s Kolemin estate (now 40 Voznesenskaya Street). His father served as a clerk of the Forest Office, and then taught natural history in the surveying classes of the Ryazan gymnasium; fellow officials considered him “red” and a freethinker. The material situation was difficult, the archive has a record of E. Tsiolkovsky’s payment of arrears for rent for the whole year 1865. Home upbringing and initial education of the children was carried out by the mother, whom the son considered a very capable and educated woman. Konstantin learned to read on his own at the age of seven by Afanasyev’s “Fairy Tales”. Biographers recognize his childhood as “happy”: apparently, he was not depressed by the family upbringing, distinguished by physical activity.

He was also attracted to natural sciences and technology: at the age of eight, his mother gave him a toy balloon made of collodion, filled with hydrogen; Konstantin was fond of launching kites, to which could be tied a box with a cockroach. In 1867, neighbors in the house were the family of Vasily Apollonovich Belopolsky, the astronomer’s own brother; his son Peter was friends with the Tsiolkovsky brothers. In the spring of 1868, Eduard Ignatyevich was transferred to Vyatka for service.

Around the beginning of 1867 (he himself found it difficult to date), Konstantin caught a bad cold while sledging in winter, the disease turned into severe scarlatina and due to complications he became almost completely deaf. This made it extremely difficult for him to communicate with everyone around him, determining the peculiarities of Tsiolkovsky’s personality and development for the rest of his life.

Education. Life vocation (1869-1880)

Vyatka. Gymnasium

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky at the age of 6-7 years old

In 1868, Eduard Ignatievich Tsiolkovsky was appointed as a stolonachal of the Forest Office in Vyatka. Probably, the transfer was also due to the fact that relatives lived in this city, in particular, his elder brother Narciz. In addition, there were many exiled Poles in Vyatka, who served in various departments. The family’s stay in the city lasted until 1878; the Tsiolkovskys lived in the Shvetsova estate, and in 1873-1878 – in the house of the Shuravins. In the fall of 1870, the mother Maria Ivanovna Tsiolkovskaya passed away, the exact date of her death is unknown. According to the 1873 household census, the Tsiolkovskys could afford to keep a maid and a cook; a sister-in-law, Ekaterina Ivanovna Yumasheva, also lived with them. As of 1876, E. I. Tsiolkovsky held the post of provincial surveyor in the rank of court counselor, having 600 rubles annual salary and an additional 200 “feed” rubles.

The younger Tsiolkovsky at the age of 12 – in early August 1869 – was given to the Vyatka Classical Gymnasium, while exempt from tuition fees.

The consequences of the disease – lack of clear auditory sensations, separation from people, humiliation of crippling – dumbed me down a lot. My brothers studied, I could not. Whether this was a consequence of dumbing down or of a temporary unconsciousness peculiar to my age and temperament, I still do not know.

Н. Kochetkov noted that the skills of self-education and respect for theoretical knowledge Tsiolkovsky was instilled precisely in the gymnasium. Nevertheless, judging by the surviving journals, Konstantin was characterized by vivacity of character, was repeatedly subjected to disciplinary penalties, and because of failure in Latin, Greek and German, as well as Russian languages and the Law of God, was left in the second grade for a second year. The result of isolation was more or less haphazard self-education, which Tsiolkovsky diligently engaged in since the age of 14 or 15.

Predominantly it was reduced to arithmetic, geometry and physics, Konstantin learned to work on a lathe, began to think about building an aerostat. His father, obviously understanding the gifts of his son, decided to send him to Moscow. In July 1873, Konstantin was officially dismissed from the fourth class of the gymnasium “to enter a technical school”. He went to Moscow with a letter of recommendation from Belopolsky. He was probably accompanied by his father: a document dated July 24, 1873, according to which E. I. Tsiolkovsky received a 29-day vacation, has been preserved.

Moscow

The Moscow period of Tsiolkovsky’s life is scarcely documented and on the slope of days was strongly mythologized by him. For life Konstantin was allocated about 10 rubles a month (occasionally managed to get 15), and he tried to spend a minimum of money on himself, and for three years literally lived on bread and water at the rate of 3 kopecks a day; the remaining funds – quite sufficient at the prices of the time – were spent on books, materials for physical and chemical experiments, and the like[34]. The extreme asceticism of life did not prevent the first romantic aspiration: the landlady – laundress – told about the amazing “ascetic” – the guest to his clients – a wealthy merchant family, denoted in the memoirs as “Ts” (Tsyplakov or Zimmerman). As a result, between the well-read young lady from a wealthy family (her name was never mentioned) and Tsiolkovsky arose a correspondence that lasted about two years; it was terminated at the will of her parents. According to the results of the research of V. N. Kochetkov, Tsiolkovsky lived on Petropavlovskaya Street near the Zimmermans’ house in Lefortovo. According to Tsiolkovsky himself, he studied in the Chertkov public library, where he was welcomed by “the famous ascetic Fedorov, a friend of Tolstoy and a marvelous philosopher and modest”, in particular, issuing books banned by the censorship. According to other judgments Tsiolkovsky, he became acquainted with the philosophical views of Fedorov only many years later[38]; in addition, in the library he worked only since 1876, and could not have a particularly profound influence on Tsiolkovsky[39]. V. Kochetkov suggested that Tsiolkovsky could study at Nikolai Petrovich Malinin, a teacher of the Model School at the Moscow Teachers’ Seminary. In other words, the degree of Konstantin’s independence in the capital was excessively exaggerated, and E. I. Tsiolkovsky acted through A. I. Belopolsky and sought to prepare Konstantin for the future. Belopolsky and sought to prepare his son for admission to the Moscow Technical School. Further, apparently, the teachers recognized in Konstantin a pedagogical gift and proposed to change the program of classes; at least, this explains well the subsequent events.

Н. Moiseyev, analyzing Tsiolkovsky’s classes of this period, noted that he “set himself in this period a number of problems, new, not read out, perhaps, but invented and only inspired by reading. All these problems are such that they require some kind of mechanical design, solution”; this is labeled as “the study of the fundamentals of physics and mechanics by means of the method of etude technical design.” Nevertheless, G. M. Salakhutdinov did not consider his mathematical training and the education he received as any kind of fundamental. “Having understood elementary algebra, he had no solid skills in trigonometry and in four attempts to find trigonometric functions in a triangle he made two mistakes. From higher mathematics, he was able to differentiate and integrate simple expressions, as well as arrange functions in series.” Significant influence on the formation of Tsiolkovsky had the works of D. Pisarev, from whom he took the methods of popularization of scientific knowledge; in a sense, Konstantin Eduardovich experienced and literary influence of the structure of figurative speech Pisarev.

Vyatka – Ryazan

In 1876, Konstantin returned to Vyatka, and the reason usually given in biographies that his father could no longer support him is refuted by the receipt of Eduard Ignatyevich allowance of 100 rubles per annum for the upbringing of children, paid for six years. With the help of his father Tsiolkovsky got a tutor in algebra and geometry, and enjoyed success because he was able to explain the subjects in an accessible way and demonstrate them on handmade models. Konstantin never bargained, so his fees ranged from 25 kopecks to rubles per hour of lessons. Earnings became regular, allowed to accumulate a known amount and rent a separate room for a workshop-laboratory. His elder brother Alexander, having graduated from the Forest Institute, served in the neighborhood in Slobodsky. On November 7, 1876, the younger brother Ignatius, a promising sixth-grade gymnasium student, died of typhoid fever. Earlier, in 1875, the younger sister Ekaterina died, buried next to her mother. Finally, in 1878, Eduard Tsiolkovsky retired, and decided to return to Ryazan. By that time his father was also suffering from deafness and some kind of nervous disease causing “concussion of all members and withdrawal of the legs for a long time”. Aunt E. I. Yumasheva, who was 51 years old, and 13-year-old sister Maria remained with the father and Konstantin. The elder brother Alexander in the same year was transferred to Bobrovsky district of Voronezh province, and brother Joseph (who had previously graduated from the Kazan infantry school) returned from the front of the Russian-Turkish war in the rank of staff-captain.

The Tsiolkovskys settled in a rented apartment in the house of N. N. Trubnikova on Sadovaya Street. There was no income from lessons in Ryazan, the accumulated sum melted away quite quickly. November 16, 1878 Konstantin passed a medical commission and was exempted from military service due to deafness and developed myopia. On his birthday Tsiolkovsky passed an external examination for the title of teacher of public schools. The most difficult was the test in the Law of God (September 5, 1879), for which he received an excellent grade. Examination in Russian language on September 12 brought a satisfactory grade, the highest score was certified test in arithmetic and algebra (September 13); the trial lesson was also considered satisfactory by the commission.

However, the appointment was delayed for four months, during which Konstantin managed to get a job as a tutor in a landowner’s family, in the library of which were “Fundamentals of Chemistry” Mendeleev. From this period the first manuscripts with projects of flying machines, as well as reasoning about gravity and centrifugal force, some drawings and calculations have been preserved. In the village he also became infatuated with a peasant girl, whom he taught additionally literacy. January 24, 1880 came the notice of appointment Tsiolkovsky teacher of arithmetic and geometry in Borovskoe city school. His father was so pleased with his son’s success that at his own expense “built” him a uniform and overcoat, which cost 32 rubles, which Konstantin returned to him on vacation from his first earnings. Eduard Ignatievich Tsiolkovsky died suddenly on January 9, 1881, in his sixty-first year of life. The letter about it reached his son too late, he did not even attend the funeral; this was the end of Konstantin Eduardovich’s family ties.

Borovsk (1880-1892)

Marriage

Arriving in Borovsk, Tsiolkovsky initially stayed in a hotel, and the next day he was invited to the house of the head of the school A. Tolmachev. Having received the lifting money, the young teacher rented a room in an empty house, in which the first night he almost caught fire and was able to cancel the contract. Then he rented an apartment (consisting of a hall, a front room, and two side rooms) from Fr. Eugraf Sokolov, a priest of the Uniate Church of the Intercession. The house belonged to the parish and was located on the outskirts, on the old Kaluga road. The apartment was quiet and suitable for scientific studies, although Father Evgraf “drank heavily”. In addition, the Sokolov family invited Tsiolkovsky to dine with them. Despite his deafness, Tsiolkovsky quickly got along with his colleagues at the school, especially the caretaker A. Tolmachev, the teacher S. Chertkov (who became the first publisher of Konstantin Eduardovich’s works), and others.

Christmas church in the village of Roshcha, where Tsiolkovsky was married

On August 20, 1880 Konstantin Tsiolkovsky married the daughter of his landlord – 23-year-old Varvara Sokolova. The wedding took place in the village of Roscha, four miles from the city; the guarantors were the history teacher I. Chistyakov and N. Tolmachev (a teacher at the diocesan school), as well as the priest Eugraf Sokolov and his son – seminarian Ivan. On the same day Tsiolkovsky bought a lathe from the merchant Voropyannikov and brought it home.

In his deathbed memoirs he described his marriage as follows:

I married <…> without love, hoping that such a wife will not spin me. Will work and will not prevent me from doing the same. This hope was quite justified. Such a friend could not exhaust my strength: firstly, did not attract me, and secondly, and herself was indifferent and passionless. I had an innate asceticism, and I helped him in every possible way. With my wife we always and all our lives slept in separate rooms, sometimes through the hay. <…> Before and after my marriage I knew no woman but my wife. I am ashamed to be intimate, but I can’t lie. I’m talking about the good and the bad. I gave marriage only a practical meaning.

Tsiolkovsky himself recognized that his marriage was unhappy, and the atmosphere in the family – depressing. Konstantin Eduardovich by nature was despotic and in principle did not tolerate objections; at the same time, to the best of his ability to help his wife in the household (even sewed himself and her shirts on a sewing machine), although over time, everything that distracted him from his own activities, irritated more and more. There was no money for servants, and most of his needs (including preparing supplies for the winter) had to be met on his own. The people of Borovsk considered the teacher’s wife a “great martyr”. Konstantin Eduardovich and Varvara Evgrafovna had seven children: the eldest daughter Lyubov (1881-1957), four sons in a row – Ignatius (1883, committed suicide in 1902), Alexander (1885-1923, also committed suicide), Ivan (1888-1919). Already in Kaluga were born the youngest son Leonty (1892, the next year died of whooping cough), and two more younger daughters – Maria (1894-1964) and Anna (1897-1922). The autobiography says: “from such marriages children are not healthy, successful and joyful”.

Teaching and research activities

Tsiolkovsky Museum in Borovsk

After the death of A. S. Tolmachev, E. F. Filippov became the caretaker of the school, with whom Tsiolkovsky did not develop relations. Nevertheless, his pedagogical talent attracted students, he never abused punishments and did not raise his voice, was able to tell and explain[59]. At the same time, the usual way in the school was a way of additional income: exhibited a “deuce” for the quarter or parents were notified of the incomprehensibility of the offspring, which required classes beyond school[63]. Being a nobleman, Tsiolkovsky was a member of the local Noble Assembly, got together with the district leader of the nobility D. Y. Kurnosov, and rehearsed his children. This allowed to protect the teacher from the arbitrariness of superiors. Soon, however, the diocesan authorities demanded a report on his reliability and attitude toward Holy Scripture; the document was submitted by his father-in-law Fr. Eugraf, as well as his colleagues at the school[64]. After the departure of his father-in-law from the city, the teacher in 1883 had to look for another apartment, and then to move again – to Kaluzhskaya Street. Tsiolkovsky’s neighbors were outstanding people, including local local historian N. P. Glukharev, court investigator N. K. Fetter, who owned a large library, and enthusiast I. V. Shokin, who grew lemons and oranges in the greenhouse and launched flying models with Tsiolkovsky. Konstantin Eduardovich gained a lasting reputation in the city as a crank, which was confirmed by his eccentric antics. In addition to night fireworks and the launching of a kite with a lantern, he could use a vacuum pump (“which perfectly reproduced obscene sounds”), when the apartment owners gathered a company; sometimes he invited lazy visitors to “taste the invisible jam,” launched an electric machine and hit the guests with an electric current. His habit of humming while working in the workshop was almost unbearable for the household. In a sense, he was a vivid embodiment of the image of an enthusiastic loner passionate about science.

In 1882-1883 Tsiolkovsky wrote his first scientific papers on the kinetics of gases and aerodynamic similarity (both not preserved). The manuscript of the first paper was reviewed by P. P. Fan der Flit, who appreciated the enthusiasm and abilities of the provincial teacher; as a result, Tsiolkovsky was admitted to the Russian Physical and Chemical Society. In 1884 Tsiolkovsky was promoted to the rank of provincial secretary (with seniority from March 26, 1880), and from November 8, 1885 to the rank of collegiate secretary. On December 23, 1886 he was promoted to titular counselor. The years 1886-1887 were fruitful for Konstantin Eduardovich – he completed the calculations of a large controllable balloon, and also wrote the story “On the Moon”. In the spring of 1887, Borovsk was also visited by P. Golubitsky, and impressed by the acquaintance, organized Tsiolkovsky’s trip to Moscow. There in the Polytechnic Museum at a meeting of the Society of Amateurs of Natural History Konstantin Eduardovich read a report on a metal balloon. After returning, March 23, 1887 Tsiolkovsky house burned down (neighbor-coal burned carelessly hay barn), lost the library and almost all the property. The teacher for a long time plunged into depression, which outwardly expressed itself in complete impassivity. The new house was flooded in the flood of 1888, the water from the basement did not leave all summer and washed out the porch. Probably to this time belonged Tsiolkovsky’s first visionary experience – he had a vision of a regular four-pointed cross in the clouds as “proof” of supernatural existence. In the fall it was possible to move into a comfortable apartment on Molchanovskaya Street (the furnishings were inherited from the previous owners), the payment for which was 6 rubles a month – a quarter of the teacher’s salary. Daughter Lyubov was placed in the gymnasium, other children were taught by the father himself; according to memories, if in the school he was calm and patient, then to his children he made excessive demands, was hot-tempered, sometimes broke out into abuse, for a misbehavior could put in a corner or not let out of the house for a week. From the children required unconditional obedience.

In 1889 Tsiolkovsky was awarded the rank of collegiate assessor (seniority from March 23) and continued to improve his pedagogical experience. In 1890 he developed new curricula in arithmetic and geometry for grades 1-3, approved by the Pedagogical Council of the Borovsky school. In the summer of 1890 the trustee of the Moscow school district offered Tsiolkovsky a transfer to the Vladimir school, he agreed, but the transfer did not take place. Konstantin Eduardovich finished the project of a metal airship, reported on October 23 at the meeting of the IRTO; the project was approved, but funding was denied. In 1891 Tsiolkovsky took up the project of an airplane sent to N. E. Zhukovsky, who spoke quite favorably about it[69]. Finally, on January 27, 1892, the director of public schools in Kaluga province, D. С. Unkovsky petitioned Moscow to transfer Tsiolkovsky – “one of the most capable and diligent teachers” – to Kaluga. On February 4, the petition was granted; the salary was to be 36 rubles a month. The town of Borovsk gave the teacher a solemn send-off: the boys’ choir sang “Many Happy Summers”, the teachers’ group gave a farewell.

Kaluga (1892-1935)

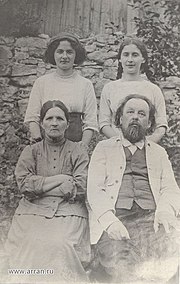

K.E. Tsiolkovsky’s family in Kaluga

К. E. Tsiolkovsky with a mirror July 6, 1902. Photo by A. Assonov

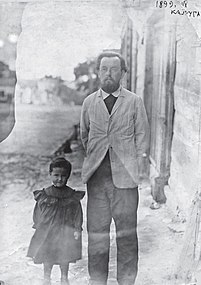

Tsiolkovsky with daughter Maria, September 1899. Photo by A. Assonov

The Tsiolkovsky family during the flood of 1908. Photo by K. Tsiolkovsky (self-timer)

Tsiolkovsky with his wife and daughters in the summer of 1914. Photo by A. Assonov

House and Scientific and Technical Projects (1892-1917)

Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky spent all his maturity and old age in Kaluga: from 35 to 78 years. Together with Tsiolkovsky, his Borovsk colleagues S. Chertkov, E. Kazansky and V. Ergolsky were transferred to the provincial center. E. Yeremeev, a geography teacher from Borovsk, helped to rent an apartment on Georgievskaya Street in Timashova’s house. From February 4, 1892 Konstantin Eduardovich served as a teacher of arithmetic and geometry in the district school. August 8 in Kaluga was born Tsiolkovsky’s youngest son Leonty. The next year the family moved to a more comfortable apartment on the same street; in this house were born younger daughters. Tsiolkovsky maintained friendly relations with Borovsk district leader of the nobility D. Kurnosov, so the summer of 1893 spent in his estate, practicing the offspring of Dmitry Yakovlevicha; one-year-old son Leontius died of whooping cough in the absence of his father. The main content of Tsiolkovsky’s life in the second half of the 1890s was his work on a metal balloon, the construction of a wind tunnel in 1897. Tense work led to a serious illness, which in the fall of 1897 was complicated by peritonitis. Thanks to the diligence of doctors V. N. Ergolsky and I. A. Kazansky, the operation was successful and Tsiolkovsky survived, but apparently suffered clinical death.

In his memoirs he wrote: The last thing I remembered was the state of falling into some abyss, and then a dark cloud enveloped me. How long I stayed in oblivion, I do not know. <…> Since that day I know what nothingness is – it is senselessness, absence of all sensations and thoughts, and consequently of consciousness itself.

Since 1899 Tsiolkovsky taught additional physics at the diocesan women’s school, a closed educational institution for the children of clergy. In the same year, he once again tried to draw the attention of the Academy of Sciences to his work on aerodynamics, sending a petition to promote experiments, and as a result, in the next year, 1900, received from St. Petersburg 470 rubles, on which he was able to build a new wind tunnel. In addition, teacher Tsiolkovsky received a pension of 324 rubles a year for 20 years of meritorious service. In May 1903, the work “The study of world spaces by jet devices” was published. Further there was a tragedy: 19-year-old son Ignatius, a student at Moscow University, committed suicide on December 2, 1903 by taking potassium cyanide. Father went to Moscow for the funeral, lost consciousness there, and with difficulty returned to reality. The experience became the basis for writing Ethics. The money for Ignatius’ education allowed his older sister Lyubov to graduate from the Higher Women’s Courses.

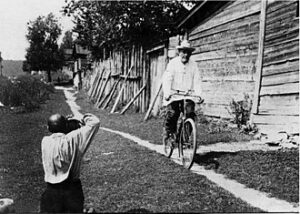

К. E. Tsiolkovsky on a bicycle in 1932. Photo by F. Chmil

May 5, 1904 Tsiolkovsky was able to buy his own house on Korovinskaya Street with the money he had saved. Initially it was a one-story building with one room (it was divided into two parts) and haylofts. Gradually an annex with two windows and a second floor – “light room”, with a workshop and library of the owner of the house, were added. In the spring of 1908, the house, located in a lowland, was badly damaged in a flood, the water level in the room exceeded a meter; all the property was soaked. The library then had to be dried leaf by leaf. According to the memories of the scientist’s daughter Maria Konstantinovna, in the house the whole routine was devoted to its owner. The rhythm of life was determined by the occupations of the father-teacher and daughters, who studied in different gymnasiums (private M. Shalaeva and state provincial). Dinner was always eaten by the whole family. Since in church schools holidays were not school days, after church services Tsiolkovsky was engaged in scientific work. He also liked to ride a bicycle.

In the sources and modern historiography there are contradictory accounts of Tsiolkovsky’s relations with Kaluga residents. It is usually mentioned about the lack of understanding of his ideas, which were considered “empty fantasy”, and his daughter Lyubov Konstantinovna in her memoirs “Next to Father” directly asserted that the townspeople called him “a crank, engaged in trinkets”. On the contrary, in the teacher’s environment of Kaluga Tsiolkovsky was evaluated extremely highly, and the head of a private real school F. M. Shakhmagonov directly certified him “as a man of outstanding”. The situation began to change in 1896-1897, when a competition was announced in the United States for the creation of a flying machine suitable for the transportation of people. In the “Kaluga Gazette” appeared a voluminous article by P. M. Golubitsky “About our prophet” with an appeal to help Tsiolkovsky in his research. After the publications of the early 20th century and correspondence with the Academy of Sciences, Tsiolkovsky’s reputation improved somewhat, he willingly invited the curious to his home, demonstrated his airship models and distributed brochures. One of his closest friends was V. I. Assonov, whose friendship was later passed on to his sons Alexander and Vladimir Assonov. The Assonovs’ social circle also included enthusiasts of Tsiolkovsky’s work, P. P. Canning (1877-1919) and S. V. Zemblinov. V. Zemblinov. According to the latter, Konstantin Eduardovich’s ideas in the 1910s were popular among the engineering staff of the Syzran-Vyazemskaya railroad management. The scientist was also supported by the Terenin family, whose youngest son A. N. Terenin later became an academician.

Tsiolkovsky in 1909

Tsiolkovsky’s work on the design of an all-metal airship, reviewed by leading Russian specialists (including Zhukovsky and Rykachev) attracted the attention of the newspaper Russkoye Slovo. The editorial board even announced a fundraiser to continue the work, collected about 500 rubles, but they never reached Kaluga. On the initiative of N. E. Zhukovsky, Tsiolkovsky was elected in 1904 as a member of the Society of Amateurs of Natural History in the physical department. May 6, 1906 Tsiolkovsky was awarded the Order of St. Stanislav III degree “for his successes in the pedagogical field”. At the end of the year Tsiolkovsky’s older brother Alexander, who had served as a manager of state property in Taurida province, passed away.

Tsiolkovsky’s work in the field of aerodynamics and resistance of materials for all-metal flying machines, which were conducted during the decade, prompted him to take up the registration of patents. On June 26, 1909, an application was filed with the Department of Commerce and Manufactures of the Ministry of Finance for a movable joint of metal sheets of the airship skin. Similar patent applications in Germany and Great Britain were filed by mid-December of the same year. Due to the costly procedure of registration, in January 1910 Tsiolkovsky applied for a grant to the Society for Assistance to the Successes of Experimental Sciences and Their Practical Applications, and asked N. E. Zhukovsky to apply for the same. In May, the Society’s Council allocated 400 rubles to the inventor for the construction of a visual model. In parallel, applications for patents for joining the sheets of the all-metal balloon shell were filed in Belgium and Sweden during 1910, in December – and in Italy. In general, Tsiolkovsky was not able to find funds for patenting, although by 1911 he had filed patent applications in Austria and the USA, and an application was accepted in Russia.

Publication in French in the journal “L ‘Aeronaute” markedly increased interest in the works of Konstantin Eduardovich in his homeland. The Kaluga Society for the Study of Nature of the Native Land elected Tsiolkovsky its honorary member. In 1913 Tsiolkovsky met Ya. Perelman, who was primarily interested in the ideas of conquering outer space. Tsiolkovsky tried to interest the military department in the project of airship, in 1914 he participated in the work of the III All-Russian Congress of balloonists (the report was made by his admirer P. P. Canning). By 1914 N. E. Zhukovsky and V. N. Vetchinnikov finally gave a negative opinion on Tsiolkovsky’s works and recognized their financing as inexpedient.

During World War I, Tsiolkovsky engaged in utopian projects to transform the transportation system and create a common language. In 1915, his petition to be awarded the Order of St. Anne, III degree was rejected. On August 1, 1916 he was accepted for a contract at the Kaluga Romanov Higher Elementary School and was relieved of his duties at the diocesan women’s school. P. Canning and Ya. Perelman from this year began to actively promote Tsiolkovsky’s space projects. Finally, in the summer of 1917, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky submitted a petition for retirement and underwent a medical examination. On July 23, the petition was granted by the Minister of Public Education “in view of his long pedagogical activity” with the appointment of a pension of 35 rubles per month.

The First Soviet Years (1918-1923)

Soviet power was established in Kaluga on November 27 (December 11), 1917. Because of deafness, the 60-year-old Tsiolkovsky did not participate in the political discussions of the revolutionary year, although he claimed in his autobiography that he was considered a “Bolshevik”. After the opening of the People’s University in December, Tsiolkovsky gave several lectures there on the social structure of future society and the philosophy of knowledge. Life turned out to be extremely difficult: irregularly paid pension was not enough in the conditions of a sharp rise in prices, sometimes there was no firewood and kerosene, it was necessary to illuminate with rays, and family members did not starve only because the daughter Anna Konstantinovna served in the food department for 270 rubles. On July 1, 1918 all the old educational institutions were closed, and Tsiolkovsky lost the possibility of part-time work in the diocesan school. As a result, on July 30, he petitioned the Socialist Academy and was accepted as a fellow member with a salary of 300 rubles a month. In addition, since November 1, Konstantin Eduardovich was accepted as a teacher of the Sixth Soviet Labor School of II stage. In February 1919 Tsiolkovsky began a wide distribution of his brochures about balloons and airplanes to the headquarters of the Southern Front and on the drug committees. He managed to interest the Red Air Fleet Administration, but its commission (which included N. E. Zhukovsky), gave a negative conclusion on May 30 about the possibility of building Tsiolkovsky’s airship. October 5, 1919, Tsiolkovsky’s son Ivan died in agony from gut congestion and poisoning by spoiled sauerkraut.

Finally, on November 17 Tsiolkovsky was arrested by the Cheka and sent to Moscow. However, the reason for the arrest was a misunderstanding, and he was released two weeks later (December 2), in addition, with a petition appealed and educators of the city of Kaluga. By order of the head of the special department of the Moscow Cheka E. G. Yevdokimov, the case was investigated. G. Evdokimov the case was terminated; further arose the legend that Konstantin Eduardovich personally communicated with Dzerzhinsky. In his memoirs Tsiolkovsky claimed that the food in the inner prison at Lubyanka was better than the rations at liberty. He returned to Kaluga on a freight train, and when landing badly injured his leg and barely made it home. A strong blow after returning to Kaluga was the illness and death of P. P. Canning in December 1919; according to memories, Konstantin Eduardovich “cried with tears”. In June 1920 Tsiolkovsky was accepted into the ranks of the Society of Amateur World Scientists (although he was never able to meet its chairman N. Morozov in person), but the Socialist Academy refused to re-elect him. His pension also stopped being paid. The need to survive prompted Tsiolkovsky to appeal in 1920 to the Kiev provincial sovnarkhoz with a proposal to relocate him to Ukraine “for the use of his inventions”. This was mainly facilitated by the aviator A. Y. Fedorov, whose correspondence with him had been the cause of his arrest the previous year. In September, the authorities were ready to hand over a whole wagon for resettlement. In January – February 1921 the Kaluga gubsovnarkhoz contacted the main directorate of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Air Fleet, and on April 9 Tsiolkovsky was taken under “special guardianship” and even an initiative group of the Metal Airship Society was established. On June 20, Tsiolkovsky was enrolled in the Gubsovnarkhoz as a design technician (later a consultant) and a petition was sent to the People’s Commissariat of Education to award him academic rations and a personal pension.

On August 26, the Academic Center of the Narkompros allocated Tsiolkovsky a lump sum of 500,000 rubles in allowances, and on October 1, academic rations began to be issued in double amount. On October 22, 1921 Tsiolkovsky submitted an application requesting to be relieved of his teaching duties at the Kaluga school. On November 1, 1921 Tsiolkovsky was finally dismissed from the Soviet labor school for health reasons. On November 9, the Small Council of People’s Commissars considered Tsiolkovsky’s case, resulting in a ruling to award him a lifetime pension of 500,000 Soviet rubles per month. While the bureaucratic procedure was unfolding, on January 21, 1922 Tsiolkovsky’s daughter Anna (married Kiseleva), who was by then a member of the RCP(b), died of tuberculosis. On April 22, Gubsovnarkhoz reduced Tsiolkovsky’s rate, but instead it was pointed out “the need to find a way to support Tsiolkovsky’s work and to create around him such an atmosphere that would allow him to fully devote his time, energy and knowledge for the good of the state”. From May 1, Gubsovnarkhoz began to pay Tsiolkovsky 25 million inflationary rubles a month. The authorities took seriously the project of metal airship, and on September 29, 1922, the Scientific and Technical Committee of the Main Air Fleet allocated Tsiolkovsky 3000 rubles in gold for the construction of a working aluminum model of the aircraft. After the monetary reform in the USSR by the decision of the Council of People’s Commissars Tsiolkovsky was established pension of 75 rubles in gold per month[Note 5]. At this time there was an acquaintance of the scientist with A. L. Chizhevsky. June 28, 1923 there was a tragedy: on the grounds of depression committed suicide Tsiolkovsky’s son Alexander, who lived in Ukraine.

All-Union Glory. The last years of his life (1924-1934)

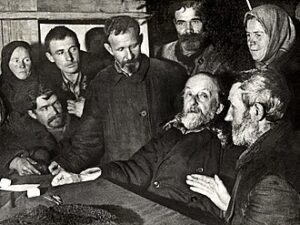

К. E. Tsiolkovsky talks with collective farmers after his lecture “When the Sun goes out”. The village of Ugra, December 2, 1934. Photo by F. A. Chmil

In 1924 at the Military Scientific Society of the Academy of Air Fleet was opened section of interplanetary communications, correspondence with which K. E. Tsiolkovsky began April 29, however, “as premature”, already in December it was liquidated. In June, the first part of the article “Life in the Interplanetary Ether” was sent to the Section; at the same time, a request for a popular science article on interplanetary communications came from the journal “Technics and Life”, especially since it was planned to place a material on this subject by F. A. Tsander in No. 13. The articles were not published. By order of the Main Air Fleet in December Tsiolkovsky finished a large model of a metal airship, which was also reported by the Kaluga Gubsovnarkhoz. The commission inspected the model on April 4, 1925, about which Tsiolkovsky himself wrote that the metal shell “failed badly (bad material and my blunders)”. On May 3, a public debate about Tsiolkovsky’s airship took place in the large auditorium of the Polytechnic Museum, attended by representatives of TsAGI, Glavvozduvozdukhoflot, the All-Russian Association of Naturalists (ASSNAT), and even the People’s Commissariat. In a press conference after its conclusion, Tsiolkovsky stated that it was necessary to build a non-flying model to practice the technology, with funding from Glavvozdukhoflot. On June 3, the technical commission of Vozdukhoflot decided to allocate 2000 rubles for work on the design of a model airship with a volume of 150 m³. On July 16, the issue was considered at the Bureau of Gosplan Congresses, and it was decided to provide conditions for Tsiolkovsky’s work so that a detailed design with technical calculations could be developed on the basis of the available schematic diagram. On August 4, the Presidium of Osoaviakhim decided to open a loan for the construction of Tsiolkovsky’s model airship, and by April 1926 it was being built in brass at ASSNAT. The Vozdukhoflot Commission on May 14 and the Bureau of the Presidiums of the Aviakhim of the USSR and RSFSR on August 9 decided that further work on the models was inexpedient. In September, a TsAGI commission (chairman V. P. Vetchinkin) was established to review Tsiolkovsky’s designs, which recognized the airship design as irrational. The consideration of the airship case continued in 1927. In November 1927, the People’s Commissariat commission on awarding personal pensions increased Tsiolkovsky’s pension to 150 rubles per month, but in February 1928, the RSFSR Council of People’s Commissars left it at the rate of 75 rubles per month[99]. In 1929, the youngest daughter Maria (married Kostina) moved in with her parents and began to run the household.

On May 31, 1928 at about 8 p.m. Tsiolkovsky had a visionary experience for the second time in his life, which he described as follows:

The sun had not yet set, but was covered by clouds. And suddenly almost at the horizon I saw as if printed, horizontally placed next to three letters: chAu. It was clear that they were composed of clouds and were at a distance of 20-30 kilometers. As I looked at them, they changed their shape. But what did these letters mean? Immediately it occurred to me to mistake the letters for Latin letters. Then I read RAY. It already made sense.

During 1928, Tsiolkovsky’s pension was increased to 100 rubles a month, but Osoaviakhim stopped paying him. In addition, due to objections from TsAGI and budget increases, the USSR Supreme National Economy Council decided to suspend work on the airship and appoint a new commission to review the project; representatives of TsAGI and the Air Force again pointed to the impracticability and futility of the work. Osoaviakhim twice petitioned to increase the scientist’s pension, and on June 1, 1928 it was increased to 225 rubles per month. In 1929-1930 Tsiolkovsky was fascinated by the idea of creating an airplane with an air-jet engine, but the technical headquarters of the Red Army Air Force on August 26, 1930 recognized the proposal as uneconomical and structurally unworked[102]. In March 1932, A. Y. Rapoport achieved the creation of a group on Tsiolkovsky’s airship in the structure of Dirigablestroy, in which he received a salary of 200 rubles from March 1.

Osoaviakhim made a decision to celebrate Tsiolkovsky’s 75th birthday, and initiated a petition to award him the Order of the Red Banner of Labor. The celebration took place in the Club of Railwaymen in Kaluga on September 9, 1932. The book by Y. Perelman about the life and scientific works of Konstantin Eduardovich was signed for printing (August 16). On August 20, Dirizhablestroy closed the topic of all-metal airship[104]. On October 17, the CEC of the USSR approved Tsiolkovsky’s awarding of an order, Osoaviakhim’s petition to award Tsiolkovsky a pension of 600 rubles per month, and the Kaluga City Council renamed Bruta Street, where Tsiolkovsky’s house was located, in his honor. On the same day in his honor held a meeting in the Hall of Columns in the House of Unions (Konstantin Eduardovich refused to come and solemn reports were read by R. Eidemann and N. Rynin), and a press conference in the hotel “Metropol”. The order was presented at a meeting of the Presidium of the CEC of the USSR on November 27, 1932.

Throughout 1933, A. Y. Rapoport sought to resume work on the construction of an all-metal airship. In the summer K. E. Tsiolkovsky gave a lecture at the Komsomol sanatorium and on July 25 gave a lecture on stratoplanes and rockets on the radio; he also spoke at a pioneer camp. The Kaluga City Council provided the Tsiolkovsky family with a new house, which they moved into on November 18. After the establishment of the Jet Research Institute in 1934, Tsiolkovsky met with its director I. T. Kleimenov and M. Tikhonravov, who was the head of one of the departments. Having learned from his grandson about the fall of a bolide visible from near Moscow, on May 14 Tsiolkovsky appealed through a newspaper to eyewitnesses to report his impressions. Around the same time, Vasily Zhuravlevlev and Viktor Shklovsky, who had been brought in to write the script, arrived in Kaluga to consult on the movie “Space Flight”. According to Shklovsky’s memoirs, published in 1963, Tsiolkovsky stated that he regularly communicated with angels, and Shklovsky himself could also do so, for he had a suitable head structure.

Death

In 1935, the Kaluga teacher’s health deteriorated sharply. Despite this, his speech was broadcast on the radio at the May Day rally immediately after the first persons of the state (it was recorded the day before in Kaluga), in which the scientist expressed his firm belief that space travel would be realized, and many of his listeners would witness it; although the speech was mainly devoted to aeronautics. On July 9, Konstantin Eduardovich was examined by Professors Luria and Gerstein, who made a disappointing diagnosis – stomach cancer. Tsiolkovsky’s condition quickly regressed: in the diary of his daughter Lubov Konstantinovna on September 4 noted that her father was “unbearably tormented”, and claimed that “tired to live”. September 7, on the eve of his departure for the hospital, Tsiolkovsky together with his daughter dismantled his personal archive, arranging papers in specially purchased for this folder; they had to write them lying down. He was tired, not having done even half of the work. Then there was a consilium of Professors Plotkin and Smirnov. On September 8 Tsiolkovsky was taken to the Kaluga railway hospital. Here at 23 hours and 20 minutes he underwent an operation. The state of health of Konstantin Eduardovich was under constant control of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks (b), the materials of the central and Kaluga press printed medical bulletins about the situation of the scientist.

L. M. Kaganovich initiated the transfer of Tsiolkovsky’s works to the state, and it was necessary to hurry: on September 13, Tsiolkovsky’s condition deteriorated sharply, although he remained fully conscious and retained clarity of judgment. The first secretary of the Kaluga District Committee B. Treivas ordered to compile the text of Tsiolkovsky’s letter (authored by journalist Petukhov), addressed personally to Stalin. Treivas visited the scientist in the hospital, convincing Tsiolkovsky to sign the letter, which was not an easy task, given the willfulness and deafness of the scientist. The text of the letter was handed over to Kaganovich in Moscow after its preliminary approval by Tsiolkovsky (the message began with the words “Wisest Leader and friend of all workers, Comrade Stalin!”). M. Selivirstova, Treivas’s wife, personally took the will to Moscow, sending a copy to the Central Committee of the Party and another to Pravda. The transmission of the letter to Stalin was delayed because the issue of the original was not resolved[Footnote 6]. After a personal order from Kaganovich, the leader received the original at 11 p.m. on September 16. A reply government telegram to Tsiolkovsky was published in Pravda and Izvestia on September 17 and was delivered to the hospital. Tsiolkovsky, despite his weakness, was deeply impressed, even rose from his bed, and dictated a reply telegram:

“Moscow, to Comrade Stalin. I am touched by your warm telegram. I feel that today I will not die. I am sure, I know: Soviet airships will be the best in the world. I thank Comrade Stalin!” Then handwritten: “No measure to thank. Tsiolkovsky. September 17.”

September 19 at 22 hours 34 minutes Tsiolkovsky died. Journalist Petukhov, having received the news from the hospital, immediately telephoned to Moscow, and the TASS message came out 20 minutes later. The obituary in the newspaper Pravda was written by Karl Radek. Tsiolkovsky’s funeral in the Zagorodnoye Garden on September 21 turned into a grandiose procession, which, according to press reports, was attended by about 50,000 people – almost the entire population of Kaluga.

In 1936, at the place of Tsiolkovsky’s burial, a 12.5-meter-high obelisk monument was erected according to the project of architect B.G. Dmitriev. The pedestal was decorated with cast-iron bas-reliefs by sculptors I. M. Biryukov and Sh. A. Muratov, depicting a portrait of the scientist surrounded by schoolchildren; and a rocket projectile in interstellar space; memorial inscriptions reproducing a letter to Stalin were also placed. Varvara Evgrafovna Tsiolkovskaya outlived her husband by four years and eleven months, and died on August 20, 1940. Her grave in Pyatnitsky cemetery is lost. The youngest daughter – Maria Konstantinovna Kostina (died December 16, 1964) – became the main keeper of her father’s legacy, consulted specialists in the arrangement of Tsiolkovsky’s house-museum, the head of which for a long time was her son Alexei Veniaminovich Kostin (1928-1993).